This content originally appeared on Beyond Type 1. Republished with permission.

By Brittany Mcwilliams

Frederick Banting could not sleep. It was 2 am on the morning of November 1st, 1920, and thoughts of the day danced in his head. Just a few hours before, Banting sat preparing a lecture on the topic of carbohydrate metabolism. He had recently secured a part-time position as a demonstrator in surgery and anatomy at Western University in London, Ontario, in addition to his own flailing private practice. Banting was an orthopedic surgeon by training and had little background in endocrinology, but as he lay waiting for sleep, something sparked in his mind. Earlier that same day, he read an article in the most recent volume of the journal Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. The article stated that the blocking of a pancreatic duct by a pancreatic stone had resulted in the atrophy of the external acinar cells but not the internal islet cells. In other words, blocking the ducts of the pancreas may, Banting thought, allow for the isolation and extraction of what would become known as insulin.

The diabetic community today hails Banting a hero for his discovery and his later philosophies. His quote, “Insulin does not belong to me, it belongs to the world,” serves as a rallying cry in the fight against high insulin costs. That he, and his colleagues, chose to sell their patent back to the University of Toronto for just $1 each serves as a moral justification in the fight for insulin access. But as these two facts are widely discussed in the diabetic community, Banting himself is lost in the fray. Banting, after all, was a complex person, sometimes contradictory, but often a hero.

A Complex Person

Banting stood nearly six feet tall. He wore his straight hair parted to the left. Round spectacles adorned a prominent nose on a round face. He was well-known as a serious, sometimes quarrelsome man, so much so that an August 27th, 1923 newspaper labeled a picture of him laughing: “Whatever the joke was, it must have been a good one”.

Banting’s abrasive nature came to define the relationships he developed as he pursued the isolation of insulin. He was unafraid of confrontation, and only a few months into his time at the labs, he threatened John James Rickard Macleod over demands for a salary and better lab space. He believed in his work, writing of his conversation with Macleod: “I had given up everything… in the world to do that research… and that if [Macleod] did not provide what I asked I would go someplace where they would.” He won the argument.

But he wouldn’t win all the battles he fought in Toronto. His would not be the first successful dose of insulin used on humans, and he would come to bear grudges against his colleagues. No picture exists of Banting alongside the other three men credited with bringing insulin to production. And when Banting and Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prize for their discovery in 1923, Banting refused to accept in person because of his great disdain for Macleod.

A Savior

But perhaps the best way to understand Dr. Frederick G. Banting isn’t through his squabbles or even through his diary. The most important things to know about this struggling doctor, average medical student, and confrontational colleague can be found in the letters of his early patients. These young children saw Banting similarly to how we see him today – not as a flawed and average human being, but as a savior.

Betsy’s letter was written with the awkward precision of a young girl still learning to write. Some letters were big, others small, rarely when they should be. Perhaps she had been forced to ask for help in spelling out Dr. Banting’s name. She possibly already knew it. Either way, the thanks was evident. “I am a little girl in Texas who is taking I’letin,” Betsy wrote, referencing the original name insulin was marketed under. She went on to tell Banting that insulin, “is making me feel better and I am so happy I want to thank you.” With a few backward letters and no punctuation, another young girl, Janet Turnbull wrote, “Dear Dr. Banting, I am feeling so good and getting so much to eat. I get oatmeal and potato.”

Banting maintained close relations with some of his patients. In September 1922, Teddy Ryder turned 6. Two months prior, Teddy had become one of Banting’s first patients, and, having saved the boy’s life, Banting attended his birthday party. In 1923, Teddy wrote to Banting, “I wish I could see you. I am feeling fine now. I would like to go to Toronto to see you.” He ended his letter with drawings of a boat and two airplanes. At the age of 16, Elizabeth Evans Hughes, Dr. Banting’s most well-known patient, wrote to him asking for an earlier delivery of insulin than expected. “Unfortunately,” the batch of insulin she previously received was “not as strong” as usual. She went on to inform Banting of her life and pursuits – activities made possible only by insulin.

A New Reality

Prior to insulin, starvation diets were the only method for prolonging life in a type 1 diabetic. Children who received the diagnosis became rail-thin as they subsisted on paltry portions. Gaining weight became a particular point of pride among the children who wrote to Dr. Banting. Janet ended her letter, “Here are some pictures. Don’t I look fat? Love, Janet.” Teddy, too, mentioned his weight. “I am a fat boy now and I feel fine.” Myra Blaustein wrote to Banting of the two and a half pounds she had gained since he first gave her insulin. She signed the letter, “I remain your little friend Myra.” Elizabeth, too, wrote extensively to Banting of her journey to gain weight. “I weigh 84 ¾ pounds now, but I’m not gaining so much a week as I was… so I hope pretty soon I’ll begin growing.”

These children knew only that Banting had given them the insulin they needed to live, and Banting’s legacy has been preserved in this positive light. His interactions with the children held no echo of the bitter interactions he maintained with colleagues – the grateful letters written to him make that much abundantly clear. Banting was just a man. He had petty moments, quiet moments, moments of aggression, and moments of kindness. But on that sleepless night in 1920, an ordinary man thought up an idea that made him a hero.

Image source: University of Toronto Library

Image source: University of Toronto Library

Image source: University of Toronto Library

Image source: University of Toronto Library

Teddy Ryder Letter Citation: “Letter to Dr. Banting ca. 1923” MS. COLL. 76 (Banting), Box 8B, Folder 11, insulin:L10021. Courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.

Janet Turnbull Letter Citation: “Letter to Dr. Banting from Janet Turnbull ca 11/1922” MS. COLL. 76 (Banting), Box 8B, Folder 18, insulin:L10023. Courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.

Betsy Letter Citation: “Child’s Letter to Dr. Banting” MS. COLL 76 (Banting) Scrapbook 1, Box 1, Page 54, insulin:L10066. Courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.

Post Views: 29

Related Post

06

06 Nov

What Type of Cancer Did Morgan Spurlock Have?

Morgan Spurlock, the producer and previous CNN series have whose McDonald's narrative Super Size Me was selected for an Institute Grant, passed on from disease confusions Thursday, as indicated by his loved ones. What Type of Cancer Did Morgan Spurlock Have? The.

Read More 24

24 Oct

When Does Nutex health Inc Do Earnings Report Come Out?

When Does Nutex health Inc Do Earnings Report Come Out? Today announced that Nutex Health Inc., Nutex Health" or the "Company," a physician-led, integrated healthcare delivery system comprising of 21 state-of- the-art micro hospitals in 9 states and primary care-centric. The.

Read More 16

16 Sep

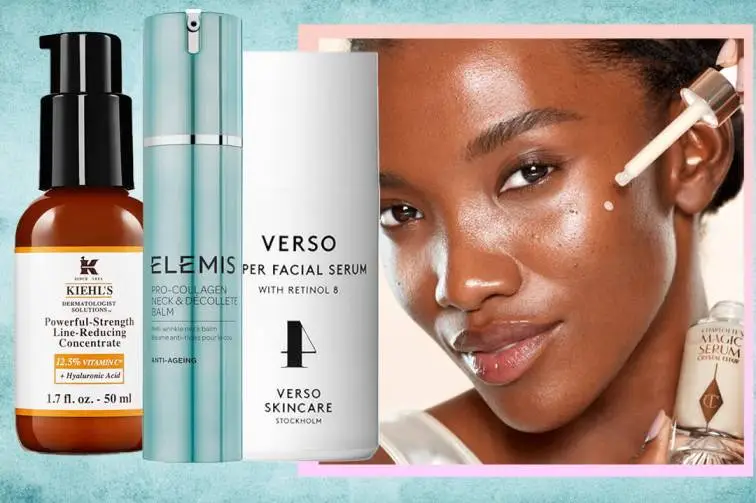

The Role of Lifestyle in Anti-Aging Skin Care Products

Looking for anti aging skin care products can feel like a hit-or-miss insight. With so many options, it can be hard to choose. These dermatologist tips can assist you with shopping with certainty. Has your skin been harmed or has it matured altogether.

Read More 14

14 Aug

7 Essential Healthy Habits to Instill in Your Kids in 2024

In the high-speed universe of 2024, raising solid and balanced kids requires a blend of shrewd nurturing and adjusting to the most recent patterns. As guardians, it's critical to instill propensities that cultivate both physical and mental prosperity in our.

Read More